Justin Landon introduced the concept of “Under the Radar” two weeks ago with his inaugural post—the goal is to give a helping hand (or, at least, a waving one) to recent books that, in our personal opinion, deserve more attention than they’re currently getting.

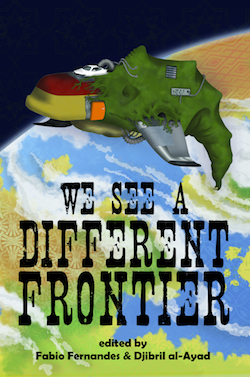

When we started bandying around the idea, I was midway through my first pick—and, to me, there couldn’t be a book that’s a better contender for this category: We See a Different Frontier, edited by Fabio Fernandes and Djibril al-Ayad—one of the best speculative fiction anthologies I’ve read this year.

The anthology follows a strict theme, that of “colonialism and cultural imperialism,” with a focus on “viewpoints of the colonized… the silent voices in history.” I’m a sucker for a themed anthology, and this is one that is deliberately different from everything else on the science fiction shelf—stories that aren’t about the inevitable Star FederationTM victory, or how Jones-the-clever-engineer saved the day. Those are hoary old campfire tales of space war and power tools. By definition, We See a Different Frontier is about new perspectives and, with them, new stories.

We See a Different Frontier comes conveniently packaged with its own critical insight—courtesy of a detailed afterword from Ekaterina Sedia—meaning I don’t even need to feign some sort of analytical perspective. Instead, I’ll cherry-pick some awesomeness:

J.Y. Yang’s “Old Domes” is my favourite story in the collection, and given how many great stories there are, that means quite a bit. Jing-Li is a groundskeeper—a profession with a very different meaning in this context. She’s trained to cull the Guardian spirits of buildings, the phantoms that inhabit structures and, in an abstract way, give them “meaning” and presence. She lures out the Guardians with the proper ritual offerings and then ends their existence: swiftly and painlessly with a plastic sword. Except, in Jing-Li’s case, her assigned prey isn’t so obliging: Singapore’s 1939 Supreme Court is refusing to go easily into that dark night. The spirit isn’t hostile as much as coy, challenging Jing-Li’s assumptions over what her occupation entails, and how successful it is.

“Old Domes” takes the reader through the full emotional cycle: first we learn how the past is being coldly replaced, then we object to it with an instinctual nostalgia, and finally, we’re led to a wonderfully optimistic conclusion, in which the past, present and future can all co-exist. This is a beautiful story.

Ernest Hogan’s “Pancho Villa’s Flying Circus” is on the other end of the spectrum, challenging any erroneous assumptions that post-colonial SF can’t be commercial—and joyous. It is wild, madcap fun with a stolen airship, steampunk madness and, er, Hollywood ambitions. It is steampunk at its finest: unrepentant anachronism and swashbuckling adventure, but, scratch that chromed surface and there’s a serious message underneath.

Shweta Narayan’s “The Arrangement of Their Parts”—a tale of sentient clockwork animals in India in the 17th century. The story balances a number of meaningful parallels: the “native” and the colonist, a machine and a scientist, a tiger and a brahmin. It is also as masterful a piece of world-building as I’ve read in some time, all the more impressive due to the tight space. By juggling history, folklore and fantasy, “The Arrangement” brings to life a setting that is begging for a series of novels (hint).

“Lotus” by Joyce Chng was one of the most thought-provoking stories in the collection. The set-up, a post-apocalyptic/post-flood world, is not particularly unfamiliar—nor is the core conceit: a young couple find a stash of a rare resource (fresh water) and must deal with the “curse” of this rare success. In many ways, this feels almost like a the set-up of a classic Golden Age SF story: a problem that’s invariably solved by our Hero becoming Lord Mayor of the New Earth Empire and leading the Great Reconstruction. But “Lotus” brings an entirely unanticipated resolution to the story—one that both satisfies and surprises. Perhaps more than any other story in the anthology, “Lotus” reinforces the need for We See a Different Frontier—an influx of new perspectives on scenarios that readers now take for granted.

Those are my four favourites of We See a Different Frontier, but, as a collection, the quality is incredibly high—from the alt-history madness of Lavie Tidhar’s “Dark Continents” (straddling the unpredictability of his award-winning Gorel and the historical insight of The Violent Century) to the classic hard SF of Fabio Fernandes’ “The Gambiarra Method” to the stomach-punch revelations of Rochita Loenen-Ruiz’s “What Really Happened in Ficandula” and the penetrative character study of Rahul Kanakia’s “Droplet,” a story of secrets and wealth.

For all its literary excellence—and again, this is a book I recommend without reservation—We See a Different Frontier: A Postcolonial Speculative Fiction Anthology is presented to readers as an anthology with an agenda. “These stories need to be read,” the editors write in their introduction, and, as much as I agree, I wonder how much being an “overtly political work” (Locus) has contributed to its under-the-radarness amongst the US and UK’s general SF readership. That is, the people who arguably need to read it the most.

I’d be curious to see what would happen, for example, if We See were to swap titles and covers with something incredibly generic—and overtly commercial—such as one of the year’s many interchangeable Year’s Best SF anthologies. The results could be fascinating.

As Aliette de Bodard says in her forward, these stories will “make a different world.” Let’s help them out shall, we? Pick up a copy of We See a Different Frontier, read it, and then share it with a friend. Or six…